by Dr. Denise J Charles. January 2022

The impact of the digital revolution on life in small island developing states has caused concern for many. The sense in which it is perhaps perceived that smaller, more dependent nations could be easily subsumed by a dominant global culture through today’s pervasive knowledge economy is not without some merit. The United Nations has sought to address this issue of cultural preservation, through its focus on intangible cultural heritage or ICH. ICH refers to the “traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants” (UNESCO, 2011). While we easily identify with dominant cultural expressions in the form of tangible artifacts and experiential creative expressions, as seen in the creative and performing arts, the fragility of ICH is perhaps best understood within the context of the unseeable. These practices, traditions and even cultural attitudes that are transgenerational must still be preserved even, as the world forges ahead with its technological development. Today’s globalization and digital revolution are both intractable; they cannot and will not be pulled back by our nostalgic leanings towards the past. The emergence of the Metaverse is a testament to the dynamic and ever-changing nature of technology and as SIDS we must find ways of defining and redefining who we are and can be even within the context of ongoing technological change.

While this technological intractability may be true, it is critical for the preservation of our cultural heritage and identity, that we, therefore, seek to carve out our own frameworks and models for digital development. A Caribbean digital sensibility must allow us to take from the world’s thriving knowledge economy, the best that is needed to secure our competitiveness on the global stage, while simultaneously building an awareness of how our culture and heritage can shape how we experience and influence the digital age. Technological advancement must not be viewed as a potential enemy poised to take our culture from us or as a force that leaves us culturally vulnerable but it should be viewed as a form of social and economic development upon which we as Caribbean citizens can act, in order to leverage and improve our own way of life.

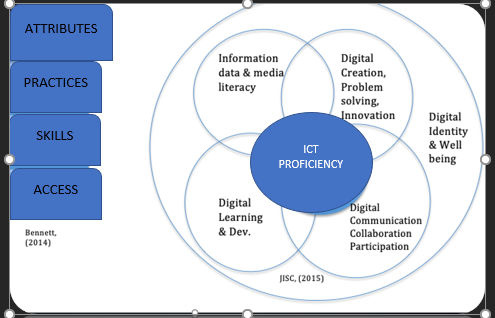

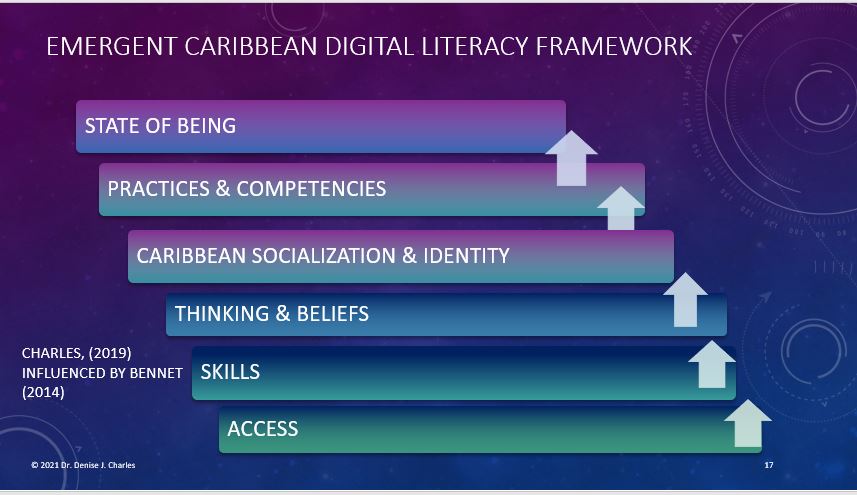

In a qualitative study that investigated the digital literacy practices and perspectives of Higher Education leaders at a Teachers’ Training institution in Barbados, several themes emerged which suggested that Caribbean variables did impact the participants’ experiences with digital development at their institution (Charles, 2019). The study’s conceptual framework was built on the Bennett (2014) model for Digital literacy which focuses on digital access, skills, practices, and attributes and on the more detailed JISC (2015) model which details the types of practices and behaviours which reflect digital competencies. A comparison of the components of these two frameworks can be viewed below.

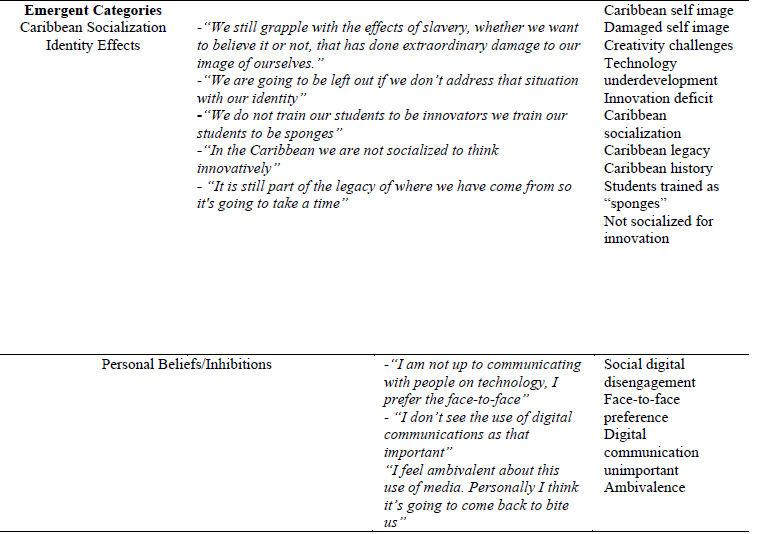

A deeper analysis of the emergent themes in this study, confirmed the presence of Caribbean variables; variables that could be described as unique to nations which had previously been colonized which could impact how people viewed or experienced digital development. While it may be argued that these variables might have been skewed by age, (participants were educational leaders) by a lack of digital experiences, and by prior perceptions, there are also intergenerational implications in these responses. These could be based on the transmission of attitudes which emerged out of a socio-cultural experience of disenfranchisement via the route of colonialism and its residual effects on the Caribbean psyche. Participants perceived that these attitudes or beliefs about the Caribbean self impacted not only how students were taught but what students themselves believed about their own ability to create and innovate. The table below reflects participant narratives that fueled a unique interrogation of digital literacy development within the context of a Caribbean socio-cultural experience.

Perceptions of challenges with innovation and creativity, the concept of a damaged self-image and identity, a tradition of rote learning and convergence to the status quo or “sponging” and perceptions of technological underdevelopment, all form a part of the unique “effects” that could influence how Caribbean citizens interface with the digital revolution. These factors could of course be further influenced by the issues of economic development and equitable access to technology which directly impact how SIDS can benefit from a rise in digital technology use.

If Prensky’s initial idea of digital natives and digital immigrants held true, (Prensky, 2001) then we would assume that these concerns referenced here, reflected the fears and trepidation inherent only in a dying breed of digital immigrants; those born prior to the digital age. The reality of COVID 19 and the need to pivot in emergency mode to online school, however, taught us differently. Educators were confronted with students who though appearing to be experts on Instagram and Tik Tok, could not upload assignments via the Google Classroom, navigate emails nor stay focused in collaborative online groups. The challenges with respect to navigating digital spaces appear, therefore, to be not only multigenerational, but multi-layered and complex. This means that the issues of digital access which lie at the foundation of most DL frameworks can be understood in terms of both socio-economic and psycho-social variables.

Both teachers and students, for a variety of reasons, across a range of countries, appear psychologically overwhelmed and out of their element in virtual learning environments, where students report issues with staying engaged or speak of the inadequacies of technologies, tools and approaches used by teachers (The Three Amigos, 2020). Gandhi (2020) also outlines issues like social disconnection, lack of eye-contact, device issues, lack of technical knowledge, peer disturbance, pandemic anxiety and teacher failure in managing the digital environment as key reasons why students dislike the online classroom. What then are the implications for digital literacy development when the thoughts, feelings and attitudes about the virtual world seem negative in an educational context and how does this influence the application of a Caribbean framework?

While digital literacy is not only necessary for virtual teaching and learning, the new normal of online, blended and or hybrid learning approaches, emphasizes its relevance and utility as a means by which virtual learning can indeed be more effective. Outside the context of school and formal learning, the very texture of life, work and leisure in the 21st Century is demanding the development of digital literacy skills at both personal and institutional levels. Differences in how we experience the digital world with leisure and social activities versus how we experience it in formal activities like online school or work, also present another valid area for future investigation.

While we acknowledge the challenges in navigating digital environments for the purposes of teaching and learning which are experienced across the globe, we in the Caribbean must also consider how our unique socio-cultural experiences must be catered to within any DL framework. Charles (2019) has therefore built on an existing framework by Bennett (2014) to suggest the inclusion of thoughts and beliefs about the digital world and the awareness of how Caribbean socialization and identity can impact navigation of the digital world (Charles, 2021).

How should Caribbean socialization, culture and self-concept be acknowledged, catered to and leveraged in digital environments? What are the specific practices and competencies best suited for the needs of Caribbean development in the 21st Century? These questions suggest the need to utilize strategic approaches in the context of a Caribbean framework to ensure the addressing of Caribbean needs and peculiarities with respect to digital development. The role that Governments, Ministries of Education or Ministries of Technology and Innovation in the Caribbean should play in leading this charge cannot be trivialized. While not exhaustive, the following list of recommendations can be important considerations in any ongoing digital development thrust, especially within the context of education:

- Address fears of digital engagement through adequate training for both teachers and students

- Provide adequate professional support to teachers to see increased use of digital environments and solutions for teaching and learning (equipment, training in use of online tools and applications, on-site technical support, pedagogical support)

- Leverage Caribbean social networks and online platforms (where they exist) to provide a space for Caribbean teachers and Caribbean students to connect in meaningful ways

- Create Caribbean Social Networks or Network groups and or Professional Learning Communities, which focus on local/regional challenges and solutions

- Incentivize digital creation or creative ideas among students at all levels through prizes/awards, recognition and development support for digital solutions to real world problems encountered through various subject discipline scenarios

- Promote Caribbean stories, images and design features in online platforms

- Encourage teachers and students to utilize Caribbean images/photos, characters, socio-cultural representations and examples in assignments (where applicable)

- Encourage digital creation through the telling and posting of Caribbean life experiences/ stories through blogs/vlogs (personal/school-level) utilizing the lens of Caribbean experiences

- Reference Caribbean values and cultural practices in discussing issues of netiquette and digital well-being

- Create new content for new knowledge generation on Caribbean life, Caribbean languages as well as on Caribbean figures/icons, (arts, literatures, sports, science/agriculture, tourism, business/finance, architecture and design)

- Encourage Caribbean perspectives on global issues and challenges and leverage on digital platforms

- Utilize digital tools and applications to promote Caribbean culture and heritage for educational and entertainment purposes; this could include the creation and sharing of Caribbean art styles (music, visual arts/photography/film, theatre, dance, culinary) and skills in wealth generation through the cultural and creative industries

- Utilize local expertise to solve/address challenges in digital development in education (e.g. app creation to facilitate local, identified educational needs)

- Build teacher digital efficacy in digital environments by providing vicarious mastery experiences through formal and informal mentorship, team teaching, exposure to local/Caribbean “experts” in the field

- Commission locally designed tools/apps for management of processes in education and in a range of sectors

- Create opportunities for the democratization of access to digital education, digital development and digital economic opportunities for Caribbean citizens

- Expose students to the opportunities for monetizing and wealth creation through digital skills development

REFERENCES

Bennett, L. (2014). Learning from the early adopters: Developing the digital practitioner. Research in Learning Technology, 22:21453. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v22.2145

Charles, D. J. (2019). Exploring the digital literacy practices and perspectives of higher education leaders and the implications for digital leadership: A phenomenological study. Doctoral thesis.

Charles. D. J. (2021). Towards the emergence of digital literacy and digital leadership frameworks for Caribbean higher education institutions; lessons learned from a doctoral study.ACHEA Symposium 2021. Retrieved fromhttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/356283551_

Gandhi, P. (2020). 11 Reasons Why Students Hate Online Classes During Corona Lockdown. Retrieved from https://www.parveengandhi.com/blog/11-reasons-why-students-hate-online-classes-during-corona-lockdown.php

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9 (5).

Retrieved from http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-

%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Prensky, M. (2009) H. Sapiens digital: From digital immigrants and digital

natives to digital wisdom, Innovate: Journal of Online Education: 5 (3)

Article 1. Retrieved from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/innovate/vol5/iss3/1

The Three Amigos (2020). 65% of students dislike virtual learning environments necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/65-of-students-dislike-virtual-learning-environments-necessitated-by-the-covid-19-pandemic-301104861.html

UNESCO (2021). What is intangible cultural heritage? Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003